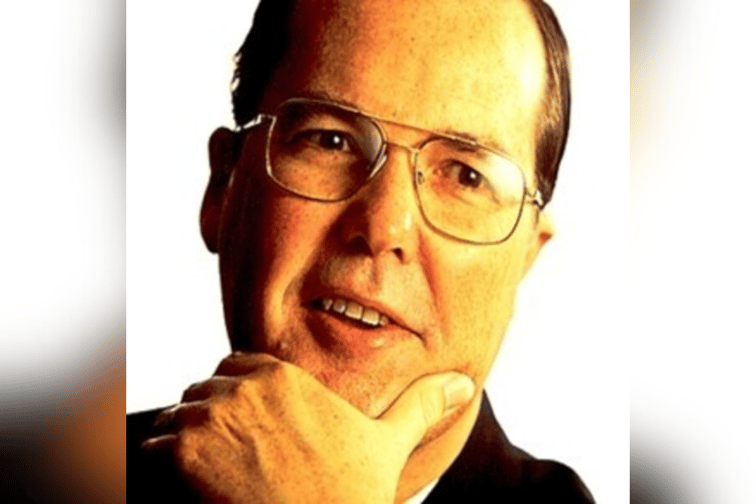

When Insurance Business asked Tony Coleman (pictured above) how industry colleagues reacted to his role in a precedent-setting court case that stopped a massive coal mine, he said many of them were pleased to see the judgment. It’s possible that few in Australia’s insurance industry have done as much as Coleman to help stop new fossil fuel projects. Given that, it’s likely that the insurers and brokerages still supporting new fossil fuel ventures, are very displeased.

In November last year, the Queensland Land Court refused permission for the proposed Waratah Coal mine, a project four times the size of the Adani Group’s Carmichael coal operation.

Coleman, who is a Munich Reinsurance director and actuary for Australia and New Zealand, said the ruling is the first time an Australian judge had rejected a mine based on the climate impacts of coal burnt overseas.

The project was stopped, he said, because the judge ruled that the burning of the mine’s coal overseas would cause environmental damage, worsen global climate change and limit the human rights of Indigenous people and children.

When asked if this case could form a precedent for the opening of new mines across Australia, Coleman was emphatic.

“I don’t think there’s any doubt, it’s a huge precedent, it was a landmark case,” he said during his presentation at the International Congress of Actuaries in Sydney.

The insurance and climate risk management implications of the evidence Coleman provided for the case are also likely to be very significant. Coleman said, as far as he knows, his evidence is the first time anyone has attempted to quantify the cost of climate change for a specific state in Australia.

Coleman was able to quantify the anticipated present and future economic impact of climate change on Queensland, including the impact of cyclones, floods, coastal inundation, bushfires and heatwaves.

“It was a bit daunting when we started,” said Coleman. “They then wanted to know, what are the costs of the deaths, hospitalizations and sickness arising from all of those as well - which was obviously quite a tall order.”

Coleman said the legal team for the coal mine put forward a cost benefit analysis that was “essentially” a net present value calculation.

“They took the view that the cost of emissions were primarily so-called scope three emissions,” he said.

The scope three emissions referred to pollution occurring outside Australia. The coal mine’s team argued that about 95% of the mine’s emissions would be in this category.

“They said, therefore, it’s [the mine’s emissions] irrelevant to the state of Queensland,” said Coleman.

However, what Coleman was asked to quantify was based around Queensland being part of the world and how these impacts on the rest of the world would impact Queensland and what that would cost.

“That was a critical hinge point, if you like, in the way in which the judgment unfolded,” he said.

Coleman said the Waratah Coal Group put a rough value on their mine - a positive net present value - of between $2.5 billion and $4.1 billion. His numbers, in contrast, showed the mining operation costing the state annually a minimum of $5.4 billion and a maximum of $19 billion.

“In other words, in one year, Queensland was going to suffer climate change costs, even on the minimum scenario, greater than the whole value of the entire Waratah coal project,” he said.

However, Coleman said this is not fair as a direct comparison because it involves the impacts of one coal mine versus all the impact on the whole of Queensland.

“But nevertheless, you can see from the numbers there is a huge difference,” he said. “The court basically looked at those numbers and thought, ‘we think we might have a problem here’.”

One of lessons for the industry, said Coleman, is how climate change risk work up until now has been “highly generalized and basically just talks about climate change risk for Australia.” For example, climate change risks, he said, are much worse in Queensland, compared to Tasmania, simply because of proximity to the cyclone threats of the equator.

“If you’re just doing a broad brush approach on a portfolio, you will miss a hell of a lot of the detail that you really need,” said Coleman.

Heatwave risks – much of it informed by recent research, including the 2019 bushfires – also formed part of the evidence. Coleman suggested this is also an area for the industry to watch given the scale of the loss of life compared to dramatic but less deadly nat cats like cyclones, floods and bushfires

“We’re talking about possibly, by 2100, more than 10,000 deaths per annum in Queensland from heatwave alone,” he said. “That’s a big number, it’s a little more than people killed by COVID in Australia.”

Coleman said one key argument by the Waratah Coal Group – that played an important role in the approval of the Adani coal mining project – was the case for substitutability.

“That is, if this mine doesn’t go ahead then some other mine will and therefore you haven’t achieved anything by stopping this mine,” he said. “Fortunately, the court finally said this is a very large mine and we just don’t think we can sustain that argument in this case.”

How do you see the insurance and nat cat risk implications of this precedent setting case? Please tell us below.